Are You Playing Fair with Copyrights?

Post By BlogPaws Co-Founder Tom Collins

The subjects of copyright infringement and fair use in blogging have been discussed in our community and I’ve participated in several of those threads, most recently in the Cat Bloggers Group — hence the image I chose to use here (from the free stock images in Canva, btw). As I suggested to the cat bloggers, I believe it is more crucial now than ever for bloggers to learn about fair use rights in order to do our best work and then protect it.

The passions displayed in that discussion reminded me that, as writers and bloggers, we often find ourselves on BOTH SIDES of fair use. As creators, we need to decide whether and how we can use others’ previous work. As authors, we want to know how much control our copyrights give us over others using our work.

As it turns out, that realization has been a shared epiphany for representatives of major creative groups attempting to agree on codes of best practices for fair use in their industries in recent years. The book Reclaiming Fair Use: How to Put Balance Back in Copyright describes two contrasting examples.

Too Much “Protection”?

Documentary filmmakers came at the question from an industry where gatekeepers (lawyers, distributors, production executives) insisted they obtain rights releases for almost all uses of previous work. The filmmakers viewed the restrictive atmosphere as the price they paid for protecting their own rights in their work.

But when researchers probed them about what impact this had on the quality of their work, they realized that they were cutting scenes, substituting music and images they could license within budget, and avoiding whole topic areas. “So the people in charge of documenting reality were not just changing reality, but avoiding it altogether,” because they did not feel confident about their fair use rights.

After a series of small group meetings around the country, here’s where the BOTH SIDES epiphany led:

[F]ilmmakers had usually come to pretty much the same place: I need fair use to be able to make work with integrity, and therefore I also need to acknowledge others’ right to use it. …

The also wanted to make sure they got (and gave) credit for free uses and payment when fair use did not apply. To move the industry in that direction, in 2005 they adopted The Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use.

Too Much “Freedom”?

From the other perspective, teachers tended to believe that in their non-profit, under-funded, educational environment, “they should not have to honor copyright ownership, if teaching kids was at stake … [and] commercial copyright holders had a moral obligation to let them use materials as they saw fit.”

Once again when pressed, the teachers had their own BOTH SIDES epiphany. They needed freedom to use others’ work to teach effectively, but also realized that when they created teaching materials, they should have some control over sharing them, including the right “to publish and sell them for use in classrooms around the country.” And the teachers’ epiphany was even more complicated. They also realized that they were teaching their students by example how copyright and fair use work. In addition, the assignments they made often resulted in their students creating works that are covered by copyright law.

The teachers’ deliberations produced their own Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Media Literacy Education (2008).

Industry Fair Use “Guidelines” Debunked

The teacher example brings up a point that arose in our recent Cat Bloggers Group discussion: the publishing industry’s older “guidelines” that purport to give simple, bright line rules about how much content you can copy safely. Several sets of these guidelines had been negotiated over the years, stating fair use rules like, “not more than 1,000 words or 10% of the work, whichever is less.”

As the Reclaiming Fair Use authors put it, “There is, of course, no grounding whatever in the Copyright Act for such a numerical limitation.” In fact, the courts have firmly established that even entire works may be copied for a variety of transformative purposes: whole songs or a play script for a parody; whole images for thumbnails; whole books for search databases. Conversely, relatively small excerpts can be infringements, if they constitute the heart of work and add nothing like commentary or criticism to it.

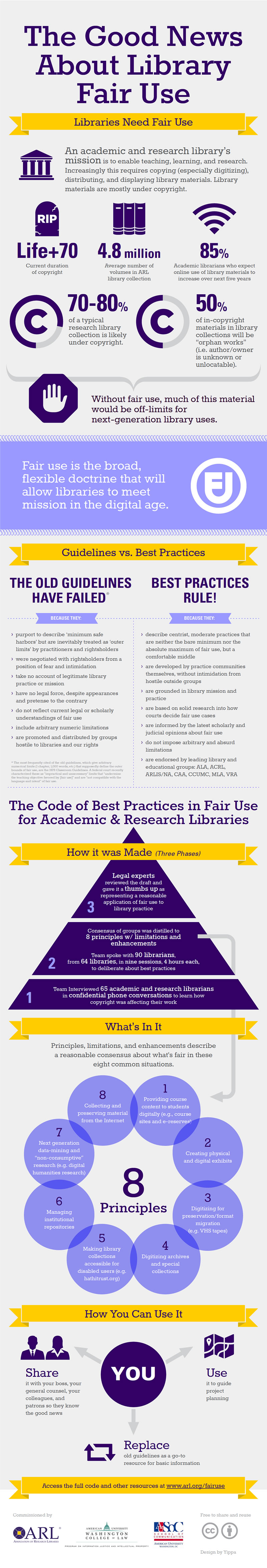

Among the fundamental problems with these industry guidelines summed up in this infographic from the Association of Research Libraries: they were “negotiated with rightsholders from a position of fear and intimidation” and rather than being treated as minimum safe harbors, they have been applied by industry gatekeepers as the outer limits of fair use (click image to enlarge; or link to full-size PDF version).

Among the fundamental problems with these industry guidelines summed up in this infographic from the Association of Research Libraries: they were “negotiated with rightsholders from a position of fear and intimidation” and rather than being treated as minimum safe harbors, they have been applied by industry gatekeepers as the outer limits of fair use (click image to enlarge; or link to full-size PDF version).

The key advantage of the newer codes of best practices over these industry-driven guidelines is that the codes identify common situations that a filmmaker or teacher may face and then provide a methodology for thinking through whether a particular use is fair and documenting the process. They stop us from pretending there are simple answers and give us a way to apply our fair use rights with greater confidence.

What’s a Blogger to Use (Fairly)?

While we don’t have a code of fair use best practices specifically for bloggers (yet?), the good news isn’t just for librarians, teachers, and filmmakers. Several more codes of best practices have been adopted and two seem especially helpful to bloggers: Set of Principles in Fair Use for Journalism (2013) and Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Online Video (2008). You can find much more on these and the other best practices documents on the Center for Media & Social Impact site.

Here’s one of the situations covered by the journalists:

SITUATION SEVEN:

Quoting from copyrighted material to add value and knowledge to evolving news

Description:

Journalists constantly derive knowledge from earlier journalism as they advance the story, contributing new information while summarizing or quoting from what is already known. Although some of this aggregation merely consolidates noncopyrightable facts, some takes verbatim excerpts of copyrighted material reporting facts or opinions. When done in ways that conform to the journalistic mission, uses of this kind recontextualize the excerpted material. Such recontextualization can be transformative, making the quotation a fair use in some circumstances.

Principle:

Fair use can apply to the quotation of earlier journalism.

Limitation:

- The journalist should make clear what she or he is adding to the existing work.

- Reviews of preexisting reports on a story or issue should where possible incorporate excerpts from multiple sources.

- The excerpts should be as brief as is reasonably appropriate to the journalist’s objectives, and, in any event, not be so extensive that they effectively replicate the original stories or function as a consumer substitute for them.

- The journalist should attribute the material in a reasonable manner. Attribution should be clearly apparent to the reader or viewer, and it should be possible for that individual to navigate easily to the original source.

- Any contractual restrictions that the journalist agreed in receiving the material would apply to quotation from it should be observed.

You should note immediately that this approach does not pretend to give you a simple answer. Get over it. The “simple” answers from previous guidelines were largely misleading and quite often “simply” wrong, when applied to real life situations.

Instead, the journalism principle above offers you a clear way to think about a situation that bloggers face in our work all the time. We are constantly learning from each other and then want to “add value and knowledge” to serve our readers and each other. The description furthers the analogy to bloggers’ work when we want to “advance the story, contributing new information while summarizing or quoting from what is already known.” (my emphasis)

When we quote others’ work, adding for example new information, contrasting viewpoints, our own perspective, the description suggests we are “recontextualizing” the quoted material, which can make it a transformative fair use.

But wait! There’s more!

The Limitations Can Help You Play Fair

Like Dirty Harry advised, ya gotta know your limitations. Sorry, but once again, the goal of these best practices is to force ourselves to think through our uses of others’ work. Every time. By doing so, we’ll become adept at explaining, documenting, and defending our uses as fair.

So let’s look at the limitations to consider in this situation. First, make clear what you are adding to the existing work. I suggest you should get this clear in your own thinking, before you start incorporating someone else’s work into yours. You might want to take notes about your reasoning on this point, until you are completely comfortable applying fair use in your work. Even when you feel confident, documenting your reasoning could come in handy if you ever need to defend a claim of infringement.

Second, where possible quote multiple sources. This goes beyond the journalists’ general preference for multiple sources as confirmation. Quoting from more than one other person’s work makes it far more likely that you’ll “add value and knowledge” by compiling, comparing, contrasting, or commenting on them.

The third one’s a biggie. “The excerpts should be as brief as is reasonably appropriate to the journalist’s objectives, and, in any event, not be so extensive that they effectively replicate the original stories or function as a consumer substitute for them.” (my emphasis) This limitation touches on every part of the four factor fair use test that’s embedded in the Copyright Act and applied by the courts. It should prompt you to think carefully about: your objectives for using another’s work; the nature of their work; the amount of the prior work you need to accomplish your objectives; and the impact your use could have on the other person.

Next, credit and link to the sources you quote. My first reaction to this one was, “Duh!” But attribution “in a reasonable manner” can go beyond a name and hyperlink. By focusing consciously on this item, you may find it reasonable to expand a bit on your view of the credit (or blame?) the quoted material deserves. That would likely bolster your claim to providing comment or criticism, core values of the fair use right.

The last item probably applies more to journalists employed in large media organizations getting news from sources like the Associated Press. But some bloggers may have subscriptions or access to paid online research, photo, or similar services and the terms of your subscription contracts may waive fair use rights and dictate how you can use those materials. Just be aware.

Simple Questions, Not Simple Answers

The authors of Reclaiming Fair Use suggest that the analysis used by the courts boils down to three questions:

- Was the copyrighted material used for a different purpose than the original, or merely a reuse for the same audience?

- Was the amount taken appropriate to the new purpose, or too much?

- Was the new use reasonable and in good faith in the user’s field of practice?

Here’s another simple way I like to think about for my own uses of others’ work: yes/no, plus!

Yes/No, Plus!

Am I quoting something to show my agreement with it? “Yes.” Am I adding my own explanation and expanding on the quoted excerpt? “Plus!”

Am I quoting to express my questioning or disagreement? “No.” Am I adding something to show why I doubt or disagree? “Plus!” The exclamation point purposefully reminds me that my own commentary or criticism — the value or knowledge I’m adding — should be the main reason for quoting in the first place.

When I’m thinking through the details of how my use may fit into one or more of the “situations” covered in the best practice codes, I put to Yes/No, Plus! question to myself this way:

Does my use qualify as comment or criticism by fitting one of these patterns? —

- Yes, and …

- Yes, because …

- Yes, but …

- Yes, if …

- No, and …

- No, because …

- No, but …

The answer isn’t always going to fit neatly or precisely into one slot. But I hope you can see the value in thinking through the answers as an essential part of your work.

As the documentary filmmakers taught us, the quality and integrity of our work goes up when we openly acknowledge “standing on the shoulders of giants.” So …

Have you had your BOTH SIDES epiphany? How do you use others’ work in your own? When others quote your work, how do you decide if they are playing fair?

One Comment